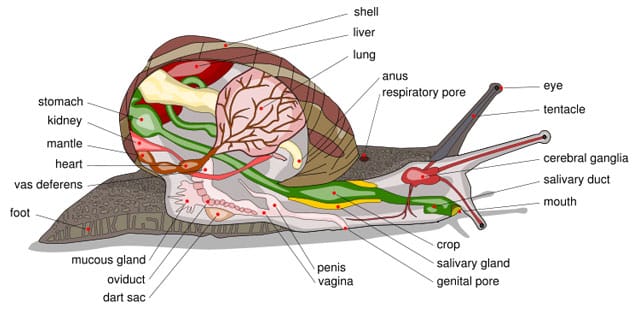

The anatomy of a land snail is very different from most other animals. Most people recognize snails by their spiral shell, but this is not the only interesting thing about them. Their body is a cluster of peculiarities and surprising characteristics not found in other animals.

The external anatomy of a snail is easily recognized by the presence of the shell, which serves as both protection and a mobile home for these creatures. The shell is primarily composed of calcium carbonate, contributing to its strength and durability. A snail’s foot, the muscular base, enables it to glide gracefully on various surfaces through rhythmic contractions. Atop the snail’s head, a set of tentacles are positioned, which not only provide a sense of touch but also house the eyes, offering the snail a basic visual perception of its surroundings.

Internally, snails are equipped with a complete digestive system, a heart, and reproductive organs tailored to their hermaphroditic nature. Despite the lack of a structured limb system, land snails do have lungs for respiration.

Despite their apparent simple appearance, snails have a very unique anatomy and physiology that support their slow-paced lifestyle!

External Anatomy

The snail shell can be very different in size and shape depending on the species.

To analyze the external anatomy of snails, we will divide their body into the shell and the soft body inside it.

Shell Characteristics

The shell of a snail is its most distinctive feature and serves as its primary means of protection. It’s a spiral-shaped structure, which varies in size and pattern across different species. The shell is made of a single piece primarily composed of calcium carbonate, and grows in a coiled pattern as a snail matures.

The main layer of the shell, called Ostracum, has two layers of crystals of the same substance: calcium carbonate. The Hipostracum is below, and the most superficial layer is the Periostracum, composed of protein.

The shell of a land snail can be very different in size and shape depending on the species. For example, some are cone-shaped while others are round. However, all snail shells have a spiral design, caused by the way that land snails produce and grow their shells.

The shell structure protects the snail from the environment and predators. It is made up of calcium carbonate (originating in the calcium in the food that the snail consumes) which makes it very strong.

The shell’s surface can contain different colors with fringe designs, but is usually brown or yellow. The shell protects the body and internal organs of the animal and has an opening to one side.

When snails sense danger around them, they hide into their shells.

Body Structure

A snail’s soft body is divided into two main parts: the head and the foot.

The head houses the mouth, brain, and sensory organs, which include its tentacles and eyes. A snail has either one or two pairs of tentacles (retractable, and equipped with tactile receptors), which have the eyes at their tips. The lower pair of tentacles works as olfactory organs, enabling the snail’s sense of smell. All land snails have the ability to retract their tentacles.

The snail’s sensory organs are multifaceted; snails employ olfactory organs to smell, statocysts to maintain balance, and eyes located on the tips of their tentacles to detect light and shadows, pivotal in the navigation of their environment. The nervous system coordinates these functions, enabling snails to interact with the world around them effectively.

Below the snail’s head is the foot, a strong muscular structure that supports the snail’s wave-shaped movement. The foot contains glands that secrete slippery mucus which reduces the friction to facilitate the snail’s movement, which is produced by rhythmical muscular contractions that make the snail smoothly “glide” over surfaces. This mucus can be seen in the “trace” that snails leaves on surfaces as it moves.

Internal Anatomy

The complex internal anatomy of snails includes a range of organs functioning together for digestion, respiration, circulation, and nervous control. The snail body lacks divisions, and the internal organs, including the gonads, intestines, heart, and esophagus, create an organic mass protected by the mantle – a protective outer layer of tissue that covers the foot and some internal organs. In some cases, the mantle also covers the shell itself to offer it additional protection.

Digestive System

The digestive system of a snail starts with the mouth (located at the bottom of its head, just below the tentacles) containing a specialized structure called a radula. Similar to an elongated sack that has several rows of tiny teeth inside it, this “tongue” has rows of tiny teeth used to scrape food particles rather than chewing.

Past the mouth, the crop serves as a storage area before the food moves to other organs of the digestive tract. The intestine completes the process with absorption and waste excretion through the anus, which is located in the lower part of the snail’s soft body.

Respiratory System

Land snails are pulmonate animals, which means that they have a lung specialized in using the oxygen obtained from breathing air from the atmosphere. Snails respire using a lung if they are terrestrial, or gills if they are aquatic.

The mantle cavity acts as a respiratory chamber where the exchange of gases occurs. This adaptation is key to their survival whether they inhabit land or water.

Circulatory and Nervous Systems

A snail’s circulatory system is open, meaning the blood flows freely through cavities and is not entirely enclosed within arteries and veins. The heart pumps the blood, delivering nutrients and oxygen to the body. The nervous system consists of ganglia, interconnected clusters of nerve cells which function as control centers, emitting neurosecretions that trigger necessary actions like the release of hormones.

While snails do not have a brain like that of dogs or humans, their cerebral ganglia act as the brain, coordinating movement and sensory information. Although this is a rudimentary brain, snails have an excellent ability for associative thinking, much more capable than most people would imagine.

Reproductive Systems

Most snail species are hermaphrodites, possessing both male and female reproductive organs. This means they can produce both eggs and sperm. While snails are capable of self-fertilization, they usually reproduce by mating with other members of their species.

These reproductive organs are typically located in the upper part of the snail’s body, near the digestive gland.

For instance, the male reproductive tract includes structures such as the testis and vas deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate gland, penial sac, penis, and penis sheath. The female reproductive system features components like the ovary, oviduct, and a specialized storage area for sperm called the spermatheca, which holds sperm until it fertilizes the eggs internally.

Most snails are hermaphrodites, possessing both male and female reproductive organs

Snail Senses

The sense of sight of snails is useful but can only detect changes in the intensity of light to recognize whether it is night or day. Snails can move their tentacles up or down to improve their ability to see.

Snails are practically deaf since they have no ears nor ear canal.

To compensate for the absence of hearing, they have an excellent associative thought capability, which helps them remember the places where they were, or where the objects in their surroundings are.

Physiological Processes

Snails exhibit fascinating physiological processes with their specialized anatomy tailored to efficient feeding and waste management.

Feeding Mechanisms

Snails utilize a unique rasping tongue-like organ, the radula, for feeding. This radula is covered with thousands of microscopic tooth-like structures, aiding in scraping or cutting food before ingestion. In their diet, which varies among species, snails might consume plant matter, detritus, or even other mollusks. The presence of a radula is crucial for the diverse feeding habits that different snail species exhibit.

Excretion and Detoxification

The digestive system of a snail ends with the anus, which is located near the respiratory opening in the mantle cavity. The process of excretion involves filtering waste through the kidneys before it is expelled. Detoxification, on the other hand, occurs as the liver breaks down toxins within the food, with waste being excreted through the intestine. This system allows snails to manage waste and regulate their internal environment efficiently.

Torsion

There is a unique process in all gastropods during their larval development, known as torsion. During this process, the body moves from the back area to the front region, which causes a rotation so that the mantle cavity, which includes the anus, shell, and visceral mass, rotates about 180 degrees and is placed suddenly above the head, making it seem that the shell is ‘backwards’.

Defense Mechanisms

Snails are equipped with specialized defense mechanisms to protect themselves against predators and harsh environmental conditions. These mechanisms involve both physical barriers and behavioral strategies.

Shell and Mucus for Protection

The shell is the snail’s primary line of defense, a hard and often spiral structure made of calcium carbonate that they can completely retract into. This barrier affords them protection from physical attacks and environmental hazards.

When snails sense danger around them, they hide into their shells. Snails spend a long time in their shell when the weather is hot and dry. If they didn’t, their moist bodies could dry out.

Along with the robust shell, snails also produce mucus, a slippery secretion that aids in locomotion and defense. The mucus can be sticky or contain neurosecretions that may deter predators.

- Shell:

- Composition: Calcium carbonate.

- Function: Provides physical protection; can completely enclose the snail.

- Mucus:

- Purpose: Aids in movement.

- Defensive barrier against predators.

Some land snail species secrete a layer of calcified or membranous septum, which when hardened blocks the entrance of the shell and is called Epiphragm.

Behavioral Responses

Snails use various behavioral responses to evade danger. The ability to detect threats using their eyes and tentacles allows them to respond promptly. When threatened, a snail’s instinct is to retract into its shell or to escape by burrowing or hiding. Another behavior, hibernation, is an extended period of inactivity snails use to survive extreme temperatures and droughts.

- Eyes and Tentacles:

- Detect threats.

- Contribute to evasive behavior.

- Strategies to evade predators:

- Retraction into the shell.

- Burrowing or hiding.

- Prolonged inactivity (hibernation) during adverse conditions.

Snail Size and Color

Snail anatomy presents a diverse range of sizes and colors, with certain species featuring notably large dimensions or vivid, eye-catching hues.

Snail Size

Snails exhibit a considerable variety in size across different species. The largest are members of the family Achatinidae. A notable example is the Achatina achatina (also commonly known as the giant African snail), a species which can grow up to 11.8 inches in length and and up to 5.9 inches in diameter. However, most snail species are much smaller.

Snail Colors

The colors of snails’ shells can vary widely, from subdued tones to bright patterns that are species-specific. These colors can include a spectrum from light pastels to deep, rich colorations.

Some species, like the Banded Snail (Cepaea nemoralis), display shells with a combination of various colors and band patterns.

Sources:

(1) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/9433231/Germaine-Greer-Snails-deserve-our-attention.html

(2) https://tamu.edu/

(3) Williams, Peter. Snail. Reaktion Books, 2012.